The Doolittle Raid

The Beginnings

Two weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt held a meeting with his top military advisers. In that meeting, Roosevelt asked for a plan to strike back at the Japanese as soon as possible to bolster the moral of America and her allies – preferably a bombing mission against the Japanese home islands.

The USAAF did not have bombers with the range to reach distant Japan from any available land bases and an attack on Japan with normal carrier aircraft was far too risky. On January 10, 1942, a US Navy captain named Francis S. Low observed Army bombers performing simulated bomb runs over the outline of a carrier deck painted on a runway. Low, who was on the staff of Admiral Ernest J. King, chief of naval operations, immediately went to King to suggest that relatively long-range Army bombers be launched off a carrier to attack Japan.

At King’s request, Low took the idea to Capt. Donald Duncan, King’s air operations officer. Over the next five days, Duncan produced a 30-page report suggesting that modified B-25 medium bombers could be launched from the deck of the new aircraft carrier Hornet to bomb the Japanese home islands. Duncan and Low contacted General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commander of the USAAF, to promote the idea. Arnold was agreeable, and assigned implementation of the plan to Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle, one of his own staff officers. A tentative departure date for the mission of April 1, 1942 was agreed upon and detailed planning began in earnest

Planning

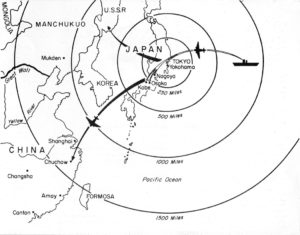

The plan – named by Doolittle “Special Aviation Project No, 1” – called for the B-25’s to launch from the Hornet 500 miles from Japan, bomb targets on Honshu, then fly to prepared bases in China.

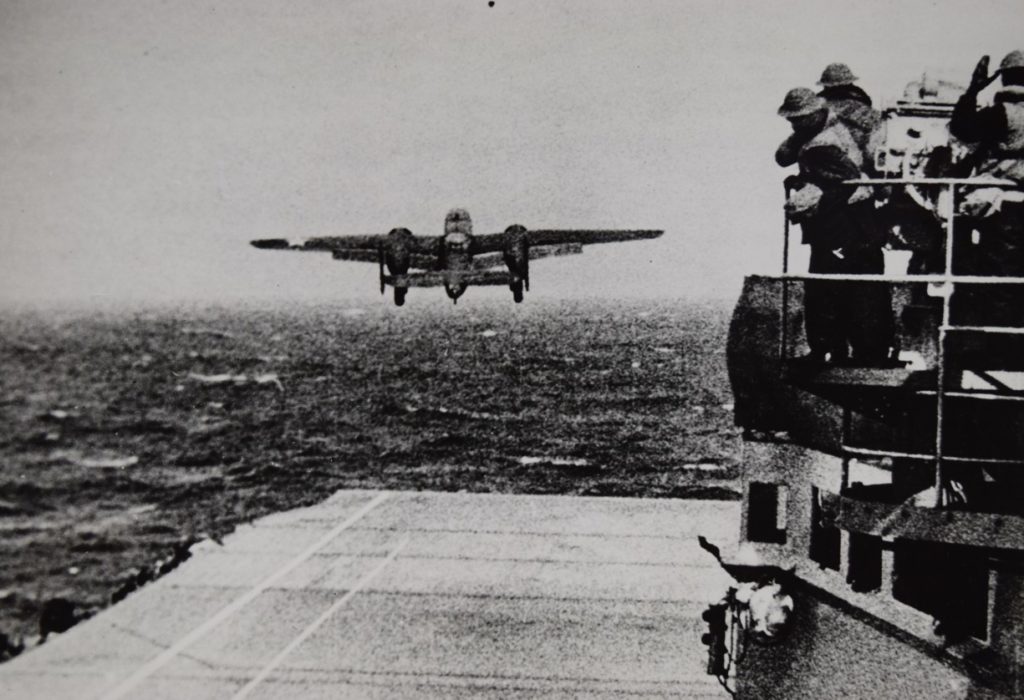

To test the feasibility of launching B-25s from a carrier, arrangements were made for two B-25 bombers to be loaded on the Hornet along with Lieutenants John Fitzgerald and James McCarthy and their co-pilots. These crews had practiced short-field takeoffs from a simulated carrier deck at an auxiliary field. On February 2, well out of sight of land, the two lightly loaded B-25’s successfully took off from the deck of the Hornet. Fitzgerald later recalled that when the bombers were spotted for takeoff he had 500 feet of usable deck and that his airspeed indicator showed 45 MPH just sitting there. He needed to accelerate only about 23 MPH.

24 B-25Bs were modified for the mission. Armor was removed; the remote control lower turret was replaced by a 60 gallon fuel tank. A 225 gallon tank in the bomb bay in the bomb bay and a 160 gallon collapsible tank in the crawl way above the bomb bay were added. These tanks increased the fuel capacity from 694 gallons to a total of 1,140.

Painted broomstick handles were fitted in the tail as dummy guns. The top-secret Norden bomb sight was removed and replaced with a “Mark Twain” sight made from two pieces of aluminum. The normal crew of 7 was reduced to 5 – pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier, and flight engineer/gunner.

Volunteers were selected from 3 squadrons of the 17th bomb group for an unspecified dangerous mission. In early March 1942, they arrived at Eglin Field in Florida for three weeks of specialized training. There they met Doolittle, who told them nothing more about their mission, only emphasizing that it would be risky. He told them if anyone wanted to pull out, they were free to do so without recriminations. None did.

The crews were trained by Navy Lieutenant Henry L. Miller to make takeoffs in 350 feet in a 40 knot wind with the plane loaded to 31,000 pounds – 2,000 pounds over its designed maximum load. They also practiced over-water navigation and low-level bombing runs using the new sight.

The crews were trained by Navy Lieutenant Henry L. Miller to make takeoffs in 350 feet in a 40 knot wind with the plane loaded to 31,000 pounds – 2,000 pounds over its designed maximum load. They also practiced over-water navigation and low-level bombing runs using the new sight.

Execution

At the end of the month, the aircraft and crews flew to McClellan Army Air Base in Sacramento, California, where the aircraft were given further modifications, and then on to Alameda Naval Air Station in the San Francisco Bay area. On April 1, 1942, 16 B-25s were loaded onto the Hornet and lashed down to the deck. The next day, just before noon, the Hornet sailed into the Pacific. As they slipped out of sight of land, the ship’s captain, Marc A. Mitscher, finally revealed their destination: This force is bound for Tokyo!

On April 17th the planes were spotted on the deck for takeoff. Doolittle’s was first, with only 467 feet for takeoff. The tail of the 16th aircraft was hanging out over the stern. Two white lines had been painted on the deck – one for the nose wheel and one for the left wheel. If the pilot kept the wheels on these lines, the right wingtip would clear the ship’s island by 6 feet.

On April 17th the planes were spotted on the deck for takeoff. Doolittle’s was first, with only 467 feet for takeoff. The tail of the 16th aircraft was hanging out over the stern. Two white lines had been painted on the deck – one for the nose wheel and one for the left wheel. If the pilot kept the wheels on these lines, the right wingtip would clear the ship’s island by 6 feet.

At 3 AM on April 18th, the Hornet received a radio message from the Enterprise: TWO ENEMY SURFACE CRAFT REPORTED. Later that morning another small vessel was sighted 20,000 yards from the Hornet. Fears that the task force had been sighted were confirmed when the Hornet’s radio operator intercepted a message from the Japanese vessel. Halsey could not risk his carriers. He ordered: LAUNCH PLANES. TO COL DOOLITTLE AND GALLANT COMMAND, GOOD LUCK AND GOD BLESS YOU.

At 8:20 AM on April 18, 1942, the Hornet’s flight deck officer flagged Doolittle to take off. With the 20 knot speed of the carrier and the 30 knot wind blowing directly down the deck, the B-25 made it off the carrier with feet to spare. At this point, the carrier was about 824 statute miles from the center of Tokyo.

At 8:20 AM on April 18, 1942, the Hornet’s flight deck officer flagged Doolittle to take off. With the 20 knot speed of the carrier and the 30 knot wind blowing directly down the deck, the B-25 made it off the carrier with feet to spare. At this point, the carrier was about 824 statute miles from the center of Tokyo.

At 12:30 PM, Tokyo time, Doolittle’s bombardier toggled his incendiaries over a factory complex. Eight other B-25s following him hit Tokyo, with the remainder hitting industrial targets in Yokohama, Nagoya, and Kobe. None of the aircraft were shot down. Only one was hit by flak, and it was not seriously damaged.

The landing areas in China were socked in by bad weather and so eleven of the crews bailed out, mostly near the Chinese city of Chuchow. Four planes crash-landed. One plane, low on fuel, landed near Vladivostok in Russia. The aircraft and its crew were interned.

Aftermath

Of the 80 crew that set out, 1 was killed bailing out, 2 were killed in crash landings, 8 were captured by the Japanese. Of these, 3 were executed, 1 died in captivity, and 4 remained prisoners until the end of the war. Four members of plane No. 7 – The Ruptured Duck were seriously injured but were helped to safety by the Chinese. Doolittle feared he would be court-martialed for losing all his aircraft. In fact, he was awarded the Medal of Honor, and promoted to brigadier general.

Of the 80 crew that set out, 1 was killed bailing out, 2 were killed in crash landings, 8 were captured by the Japanese. Of these, 3 were executed, 1 died in captivity, and 4 remained prisoners until the end of the war. Four members of plane No. 7 – The Ruptured Duck were seriously injured but were helped to safety by the Chinese. Doolittle feared he would be court-martialed for losing all his aircraft. In fact, he was awarded the Medal of Honor, and promoted to brigadier general.

The Doolittle raid was everything President Roosevelt wished for. He announced that the planes had flown from a secret base in the land of “Shangri-La” — which was actually the name of the presidential resort now called Camp David.

The intrusion of Doolittle’s bombers over Japan frightened and embarrassed the Japanese war leaders. Precious military resources were diverted to home defense, and Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the brilliant Japanese strategist who had devised the attack on Pearl Harbor, put into motion a plan to lure the American carriers into battle, destroy them, and eliminate the American threat once and for all. The result was the Battle of Midway in June 1942, where the Imperial Japanese Navy suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of an inferior US Navy force that put a stop to Japanese expansion in the Pacific, and badly damaged Japanese naval air power.

The Chinese paid dearly for the American raid on Japan. An estimated 250,000 Chinese were killed in retaliatory raids on towns and villages suspected of harboring the American fliers. The invaders made of a rich flourishing country a human hell

wrote one Chinese journalist.

Further Reading

Target Tokyo: Jimmy Doolittle and the Raid That Avenged Pearl Harbor by James M. Scott and James Scott

I Could Never be so Lucky Again by Gen. James H. Jimmy

Doolittle with Carroll V. Glines